I began my eight-day journey to Pyay or Sri Ksetra and Baikthano after receiving an invitation from an archaeologist I had met during an ICOMOS field trip in Viet Nam. He was organizing a rare study tour to the Pyu ancient cities during a brief moment of calm in Myanmar, just before the coming election. The team planned to push deeper into the country, traveling from Pyay to Beikthano to conduct fieldwork that had been impossible during the most intense years of conflict then continue to observe heritage damage in Mandalay area. Weighing both travel time and safety, I chose to join only the Pyay & Baikthano portion, a decision that still promised a deep dive into one of Southeast Asia’s oldest urban civilizations.

Before heading north, we spent a reflective afternoon in the National Museum in Yangon. In the early Myanmar gallery, glass cases displayed stone urns, bronze fittings, silver vessels, and ancient coins excavated from Sri Ksetra. The objects revealed the roots of Pyu culture and the flow of Indian influence into the region, Mahayana architectural motifs from eastern India, Amaravati, blending with Theravada traditions linked to southern India and perhaps Sri Lanka. This synthesis helped shape the spiritual and artistic DNA of the Pyu, a society that flourished centuries before Bagan rose to power.

Arriving in Pyay later next day, we headed straight for Phaya Gyi, one of the three monumental stupas of Sri Ksetra. Set amid open fields and surprisingly close to the national highway, Phaya Gyi rises in a form often compared to a rice heap, though others say its contours resemble a woman's breast. The structure rests on three massive platforms shaped as a sixteen-sided polygon. The caretaker allowed only men to climb to the topmost tier, a reminder of local customs that still guide life around sacred sites. Weathered by centuries of wind and sun, Phaya Gyi carried a quiet gravitas, my first close encounter with Pyu monumental architecture. Our exploration continued at Nagatunt Gate, a massive brick portal where the ancient city once controlled entry. The defensive design was striking. The angled walls drew invaders into a tight corridor while curved brickwork almost encircled them, allowing defenders to trap and overwhelm enemies in confined space. A short distance away was Natbuak Gate, where a small shrine honors an ancient queen believed to guard the entrance. The site reflects nat worship, a spiritual tradition unique to Myanmar that blends ancestral spirits with Buddhist belief. Further along the trail I reached Payahtuang Temple, a quiet brick sanctuary from the late Pyu and early Bagan period. Its dim interior once glowed with rows of tiny Buddha images, some of which still cling faintly to the walls.

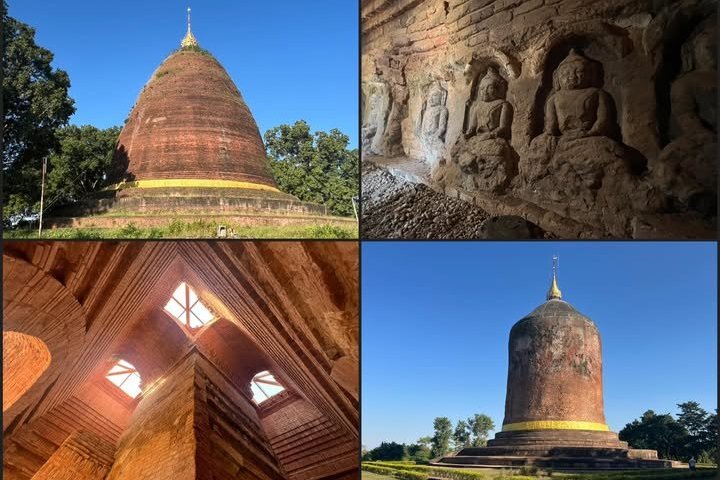

Then the Sri Ksetra site museum in Hmawzar Village, where cases of pottery shards, beads, stone inscriptions, and finely worked sculptures revealed the refinement of Pyu craftsmanship. The exhibits suggested a surprisingly connected society, one that absorbed ideas from across the Buddhist world while shaping its own artistic voice. Outside the museum, we got a special permission to enter the restricted storage hall. Inside were enormous inscription stones, some towering above us, craved in ancient Pyu and Indian derived scripts. We stopped at Rahanda Gate and the nearby Rahanda Cave Temple, a small temple hall that resembles a man-made cave. Inside, there is a row of stone Buddha images. Continuing along the historic route, we paused at the Terrace of Urns or HMA-53 Site, where archaeologists uncovered piles of hundreds of funerary vessels containing human remains. These urns, some holding the bones of animals, perhaps cherished pets, hint at communal burial practices that endured through generations. Before visiting the most famous stupa of all, the unmistakable silhouette of Bawbaw Gyi appeared on the horizon. Towering above the plains, its cylindrical brick form is among the earliest surviving Buddhist stupas in Myanmar. Bawbaw Gyi stands not only as an architectural milestone but as a visible bridge between the early Pyu world and the stupas that would later rise across Bagan.

From Bawbaw Gyi, we continued to Bebe Temple, a modest structure that reflects the transition between the Pyu and early Bagan styles. Nearby, Leymyatnhar Temple is so precariously unsafe that it is now held together by an iron frame. Despite their modest scale, these temples shed light on early experimentation with Buddhist architectural forms. The Cemetary of Queen Beikthano is a place archaeologists found many big stone urns for Pyu royalties. Our group then visited Khin Ba Mound, long suspected to be the base of Sri Ksetra’s largest temple. Numerous artifacts found in the area allowed archaeologists to partially reconstruct its visual language. Following a faint trace of the old city wall, I made my way toward Tharawaddy Gate, crossing a wet moat that left my shoes soaked and muddy. Beyond an old wooden bridge rose Matheegyagone Stupa, perched dramatically on top of the fortified wall. Its height makes it the highest point in Sri Ksetra, a commanding viewpoint over an ancient landscape. As the day softened into evening, we reached the Palace Area. At one corner of the palace wall, we paused at the spot where a massive famous Pyu metal nail was unearthed. Entry to the Palace was unexpectedly not permitted because a Buddhist ritual was underway to calm the angry spirits associated with the ancient Pyu rulers by locals!

The next morning began at Phayamar Stupa, a sister monument to Phaya Gyi. The site gains much of its significance from the discovery of five sculptures of Pyu musicians, exquisitely carved figures that offer an intimate glimpse into the cultural life of the ancient city. With this final archaeological stop completed, we returned to Pyay city to visit Shwe San Daw Pagoda, often described as a smaller counterpart to Shwedagon in Yangon. I also had a good time with Pyay's local cuisine especially Pyay Rice Salad or Pyay Htamin Thoke and Pyay Paratha, similar to Thai Khao Soi, but instead of egg noodles in curry broth, it uses crispy fried paratha as the main element. The late-afternoon light spilled across the Irrawaddy plains as I stood on the riverbank. It was a fitting end to my journey through Sri Ksetra. We continued on to Beikthano for the next stage of their study in the morning.

The significance of Pyu art and architecture lies in how clearly they mark the beginnings of Buddhist urban civilization in Myanmar. As one of the earliest cultures in mainland Southeast Asia to embrace Buddhism, the Pyu blended Indian influences with local creativity to form a distinctive aesthetic. Their towering brick stupas, delicate funerary urns, metal ornaments, and expressive sculptures reveal a society that was both inventive and spiritually rich. This cultural depth is why the ancient Pyu cities were inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List. Together they offer an exceptional window into an early urban culture with sophisticated planning, monumental religious architecture, and wide-reaching cultural connections centuries before Bagan’s golden age. What survives today is more than an archaeological site. It is the foundation of Myanmar’s artistic heritage and an enduring testament to a civilization of remarkable vision and complexity.

More on

Comments

No comments yet.