Aflaj irrigation system

The Aflaj Irrigation Systems of Oman comprise five of the some 3,000 still functioning complete settlement irrigation systems in the country.

The sites represent a well-preserved form of traditional use of shared water resources in a desert environment. The Aflaj are mainly used to make the cultivation of date palms possible. They are managed by long-standing traditional systems within the communities they serve.

Community Perspective: Aflaj can be seen in many of Oman’s towns and villages, but of the inscribed five the one in Nizwa is the most convenient to visit. The aflaj in Birkat-al-Mouz has the benefit of introducing you to traditional village life.

Map of Aflaj irrigation system

Community Reviews

Clyde

I visited 4 out of the 5 locations of this WHS on different days (sometimes doing repeat visits too) in December 2020 and January 2021. Although I had already seen some aflaj in the United Arab Emirates while visiting the Al Ain WHS, the aflaj in northern Oman are a much more elaborate irrigation network which was critical to the development of society and the agricultural economy.

Each falaj gathers water from one or more sources and channels it via a single canal into the area where it is to be used. From the canal, the water is diverted into subcanals into the fields where it sustains the tropical fruit which grows in Oman. Even though today concrete has been used to make the aflaj deeper or to extend the old network, this does not take away the remarkable engineering skills needed in ancient times to construct the aflaj, which supply water on a continuous basis in Oman's arid environment. Recently at Salut (a tentative WHS I'll review later), archaeologists has recently excavated what is believed to be the oldest known falaj out of the approximately 4100 aflaj in Oman today, of which just over 3000 are still functioning.

The water for these aflaj comes from 3 different source types: daudi (which use the underground water table to create water flow through a tunnel to its point of use), ghaili (where the surface water mostly from floods flows into wadis that are dammed and the water is diverted into a channel on one or both sides to its point of use) and aini (which collect the flow from a water spring and channel it to its point of use). The whole construction of any type of falaj required extraordinary spatial accuracy, mathematical precision for water rights to guarantee the distribution of water supply in an equitable manner, as well as divining skills. Some of the wooden tools used as time measuring devices (such as the lamad sundials) or small cairns which were used as fixed objects to take measurements using the movement of the stars were exhibited inside Nizwa Fort.

Aflaj systems are arranged in such a way that agricultural use comes after any personal requirements for people. In the majority of systems, the first water is used for drinking followed by water supplied to the men's bathing area, usually adjacent to a mosque. The women's bathing area follows next then the area for washing dishes and clothes, which is usually just below the women's area. Whenever there was a powerful sheikh or an authority, his house or fort would be placed in close proximity to the men's bathing area, possibly before it or even directly over the falaj itself as at Birkat al Mouz or Rustaq. Finally, the water from the aflaj is used for agriculture.

Especially, at Birkat Al Mouz but also in other aflaj, it was great fun to see children bathing and playing along the aflaj, while their mothers washed their clothes or dishes nearby (even though there are signs inviting people not to). Be careful to avoid embarassing moments when passing by some of the room like structures above the aflaj, as it still isn't uncommon for locals, especially elderly people, to wash themselves there! Nowadays, as Oman changes from an agricultural society to a service and industrial one, the role of the aflaj is changing too. Leisure facilities are being developed around some of them such as Falaj Daris. That said, it was hilarious to spot some washing machines connected to the falaj system of Birkat Al Mouz and it's a real pity that the old mud brick houses have been completely abandoned and have become like a ghost town.

Out of the 5 inscribed aflaj, the only one I didn't visit was Falaj Al Jeela due to its position high in the eastern Hajar mountains towards Wadi Shab (the end of the wadi can be seen from the new bridge on the Sur-Muscat highway, close to the town of Tiwi), which requires a 4x4 vehicle. Having ventured for around 300 km in total on Omani gravel roads and crazy dirt roads, I was tempted to complete all the locations but I had to give up due to quite recent major damage caused by flash floods which would have put me off even if I were driving a 4x4 vehicle.

I visited the inscribed Falaj Al Khatmeen in Birkat Al Mouz several times and at different times of the day. Make sure not to use Falaj Al Khatmeen on Google Maps as it might wrongly direct you away from Birkat Al Mouz through a restricted military airbase area; in general maps.me works fine in Oman. I parked my rental car near the Bayt Ar Rudaydah Castle and even though tourism had just restarted in Oman, immediately several 4x4 drivers rushed to the parking lot to offer their services to Jebel Akhdar. After gently refusing we headed towards the right hand side of the castle where we saw the first UNESCO WHS marker in Arabic, English, French and German. In its shade we observed a group of elderly men playing dominoes and like all the people we met during our visit in Oman, warmly welcomed us and they even offered me a place in the shade to play with them! Even though I was a bit wary because of the current pandemic, I couldn't refuse and with the necessary precautions I have gladly added yet another unforgettable experience of playing a game with locals during my travels.

After that, just behind and above the UNESCO WHS marker, we saw the point where Falaj Al Khatmeen is divided into 3 channels that create a sort of small waterfall and then kept following the falaj beneath it for a couple of hours (even though sometimes there were new walls built over it; it was easy to go round them). If you do this, you'll reach a point where you either literally walk inside or on the falaj at a height of about 10-12 metres or else you back-track a bit and walk beneath it through the date palm fields. We chose the latter, mostly because the water was a bit dirty and we knew about the risk of contracting schistosomiasis, also known as snail fever or bilharzia, which is a disease caused by parasitic flatworms released by infected freshwater snails of which there are plenty in Oman. We did the same when we reached another point where the falaj flows along a beautiful aqueduct with even though we noticed protruding stone-like stairs similar to the stairs of death at Huayna Picchu which give access to the falaj channel above. Apart from the splendid views from the never-ending crumbling ghost towns and towers (Hellat A'Sibani and Burj Al Mukhasir are the most picturesque; morning light is best for photography here) near Birkat Al Mouz, I also recommend driving just outside Birkat Al Mouz to a great panoramic viewpoint of the sea of date palms beneath the crumbling mud houses with the Jebel Akhdar mountains in the background. Head towards the highest broadcasting tower near a small fort-like structure, and make sure to climb up next to the tower as the views are really great. If you were forced to choose only one falaj to visit, I'd definitely recommend this one.

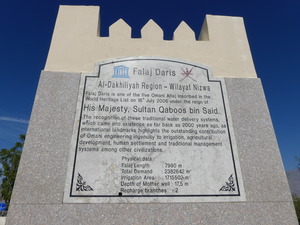

Falaj Al Daris is supposedly the biggest falaj in Oman and is located on the edge of Wadi Al Abydh in Nizwa. The main tributary for Wadi Al Abydh, the source of Falaj Daris, is the great Wadi Tanuf with its dramatic cliffs, which cuts deep into the heart of Jebel Akhdar over 20km away. In a much less natural setting, just off the road, lies a short section of this falaj which has been restored and turned into a little park and picnic area about 7km north of Nizwa where you'll also find the UNESCO WHS marker. Only about 200 meters of the falaj is visible before the channel disappears underground at either end. Indeed it is hard to spend a lot of time here even though contrary to Falaj Al Khatmeen, the water flowing here was crystal clear with plenty of fish providing free pedicure to the locals.

After our free forced extension to our stay in Oman and after driving back to Nizwa and Muscat from Salalah, we visited both inscribed Falaj Al Malki and Falaj Al Muyassar on separate days in December 2020 and January 2021. The village of Imti is near the source for Falaj Al Malki which flows to Izki and the surrounding rural villages or harats and ends in the Arabian Sea at Mahawt. The best bird eye view is obviously from high up from one of the offroad trails of the serrated peaks of Jebel Akhdar and Wadi Halfyn. The town of Izki is mentioned in an inscription in Nineveh from the Assyrian period. There are several Bronze Age tombs from the Hafit period near Izki and the adjacent village of Zukait. The exact GPS coordinates on the UNESCO website lead you to the UNESCO WHS marker which also bears the same coordinates exactly like all the other aflaj markers just in front of a mansion. Near the marker lies a tower-like structure known as Al Swaryn, similar to the great 'ice house' remains found in Ancient Merv, Turkmenistan.

Here, the concrete additions to the falaj have been tiled with limestone. Having ample time, we ventured through the very narrow roads of the different tiny rural villages near Izki following different channels of the falaj. The detailed UNESCO maps clearly show the inscribed areas and turned out to be very useful when comparing them to our GPS maps to explore the area without missing out on the best features we had in mind to explore. The area around scattered farms around the mostly abandoned settlements of Harat Al Yemen and A'Nizwar was like going back in time. Towards the town of Imti we managed to spot one of the most distinctive features of this falaj which is the inverted siphon (top right photo), which enables water from one of the tributaries to cross Wadi Halfyn passing underground rather than over a bridge, whose height would definitely not be sufficient to clear the floodwaters which have a clear impact on the area judging from the surrounding rocks and debris. To find it be on the look out of a huge police station and a small rudimental mosque with golden yellow painted domes. When you find it you'll see a concrete pavement with pebbles and behind it a sort of concrete ramp leading up to a well-like structure. You need to climb it to be able to see the inverted siphon! This was the only spot where the water in this falaj wasn't filthy.

Last but not least, we visited Falaj Al Muyassar, a few kilometers away by car from the tentative WHS of Rustaq Fort. The water for this falaj comes from a well located in Wadi Al Farai. The source water for this wadi is the impressive gorge of Wadi Bani Auf some 10km away. After passing down the town of Rustaq right beneath the Rustaq Fort, the wadi then flows north away from the jagged hills near the oasis of Jamma and onwards to the sea. The sharia of the falaj is close to the small fortress known as Burj Al Mazroui which was built to protect it and which still overlooks a vast oasis full of date palm, papaya, guava and mango, rice fields as well as banana plantations. The UNESCO WHS marker can be found just next to the point where the falaj divides into two channels. Local farmers were directing some of the water towards their fields by relocating wooden boards. Many of the fields watered by the falaj are small so using an ox is still the most ideal way to plough the fields.

We really enjoyed this WHS which provides a great overview of northern Oman and the ancient engineering feat which contributed to convert a desert landscape into a thriving oasis and which is still very much in use. Photos: top left Falaj Daris, top right Falaj Al Malki, bottom left Falaj Al Khatmeen, bottom right Falaj Al Muyassar.

Els Slots

The Aflaj are as typical of Oman as its fortresses. Nearly every village or town with roots older than Sultan Qaboos’s reign has such a falaj irrigation system. A combination of 5 out of the more than 3,000 still functioning systems has been declared a World Heritage Site. Of these 5, I visited the ones in Birkat Al-Mouz (Falaj Al-Khatmeen) and Nizwa (Falaj Daris). To both there is no formal access, they just lie in public areas.

The town of Birkat Al-Mouz is conveniently located en route between Muscat and Nizwa. When I parked my rental car at the local fort, I was immediately approached by a man in a 4x4 who asked whether I wanted a tour of the nearby mountain Jebel Akhdar. The "green mountain" is rather dry at this time of year, so I let that opportunity pass me by. For most tourists however, the mountain is a bigger attraction than a falaj.

The downhill stream of the Falaj Al-Khatmeen is easy to follow in Birkat Al-Mouz. It first appears above ground at the back of the Bait al Radidah fortress. Then it flows past the mosque, where there also are ablution spaces using the falaj (they look like dressing rooms or public toilets). Next to it is the WHS marker: a square column with the inscription text in 4 languages - Arabic, English, German, and (I am not sure about this one) French. Later in the day, I encountered the same style of marker at Falaj Daris.

The irrigation channel itself is not a spectacular sight, but coming closer to daily life in a village such as Birkat is worth the visit in itself. Birkat’s town center has some large trees that provide much-appreciated shade. A group of older men was sitting underneath them on the sand, playing dominoes. Others used the stone edge of the falaj as a bench. The channel here splits into several branches to distribute the water around town.

I continued my walk along a field with date palms. Two men were busy trimming one of the palm trees at the top so that the dates will have the space to grow. Following the advice from my Bradt Travel Guide, I went further into the village. Still, the many branches of the irrigation canal were all around to see. After fifteen minutes I arrived at the gate of a cluster of wonderfully ramshackle mud houses. Most inhabitants have left this part of the village to settle in more modern houses elsewhere in Birkat Al-Mouz. But still, some seem to be inhabited, at least I noticed laundry hanging outside to dry.

Later in the day, I made my way to Falaj Daris, just north of Nizwa. It is signposted from the road to Bahla, just keep on going till you see the brown sign. Here they have designed a park around the old falaj. There were some children playing, and young guys noisily crossed the terrain with mopeds. People swim or even bathe in this falaj. It has plenty of water in it, and it is much broader than the one in Birkat Al-Mouz. Unfortunately, there is only a short stretch of the falaj above the ground, so it is of limited interest. In Birkat Al-Mouz I spent almost one and a half hours, in Nizwa less than 5 minutes….

Douglas Langmead

United Arab Emirates - 15-Feb-15 -

I was the Resident Architect for the new Souq in Nizwa from 1990-1992, working for CowiConsult. Marfa Daris Park began as a provisional sum in a local roads improvements contract, and I was given the opportunity to come up with a design and oversee the construction of the park.

We had some prior experience for this, having designed a "pocket park" at the base of the new road bridge upstream from the souq. Up to that time the local kids had never seen play equipment, and it was very popular.

The design philosophy for Marfa Daris Park recognised its importance as a historic stopping point on the former Frankincese Trail, a place of religious significance long before there was a local mosque, where the broad steps down to the falaj were used for washing prior to prayers on a level area of stony ground adjacent. The same point, close to the emergence of the falaj out of the main wadi bed, was also a place of great cultural significance: HM Sultan Qaboos would often make stops there to show visiting dignitaries the falaj and explain its importance.

The masterplan for the park was an outcome of its geography, the religious and ceremonial importance, and the need for a local park that would be popular with the local populace. Falaj Daris itself forms the boundary to the main wadi, with a meandering path alongside that loops up to an elevated bandstand on a prominence at the western end of the park.

The stone steps down to the falaj are the focus of the religious/ceremonial axis. A magnificent Ficus Religiosa fig was located in a large circular planter with stone benches opposite the steps, and this acts as a fulcrum for a ceremonial axis that is straddled by a Reception Building in the form of a traditional tower with a watchman's apartment accommodated at the upper levels.

Gardens and lawns flank the ceremonial axis, intersected by paths and gazebos along its length and leading to an amenities building adjacent to play areas for children. The local kids love excitement, and scrambling around the hills in the area, so the play areas were zoned up the side of the wadi from safe areas for toddlers at the bottom, past a series of play areas for older kids and culminating in long slope slides on a rocky hillside shaded by canopies to protect them from the heat of the summer sun. A BMX track was formed in the original scrub and acacia trees along the hillside, much to the pleasure of the neighborhood children.

The progression from formality to the natural ruggedness of the area continued beyond the play area and culminates at the bandstand, high on the hillside and providing a visual focus at the far end of the ceremonial axis.

Wadi Daris floods regularly following thunderstorms on the jebel, so it was necessary to ensure that floodwaters would not damage the buildings, and the stone bases and level changes ensured that they were protected and kept above normal flood levels. Runoff from the roads and populated areas uphill of the park is all intercepted by stone-lined culverts which carry it beyond the falaj into the main wadi to avoid polluting the falaj water and the fish that can be seen swimming in it.

The buildings themselves were constructed in modern materials, but rendered with traditional sarooj plaster - a rich-coloured render that is made by firing large quantities of clay plugs on pyres of date-palm trunks, with the ash and fired clay crushed and mixed into a powder and mixed with water.

Recent photos attest to the success of the landscaping design carried out by Paul Cracknell, the success of the park in its unique combination of cultural and recreational facilities, and its selection as the focus of the UNESCO award.

Walter

On a trip to Oman in December 2012, I managed to visit 4 of the 5 aflaj irrigation systems on the list (I arabic, aflaj is the plural form of falaj). 3 of them are close to Nizwa, a good base to visit the area.

The irrigation system is composed of three elements, all three part of the listed proprety : first the upstream part (collection of groudwater or spring waters) that are drawn into collecting channels, mostly underground. Then a main channel (the shari’a) is usually open surface. Finally, downstream, an agricultural area irrigated by smaller irrigation channels.

As the sources and collectioning channels are mostly underground, there is not much to see. The shari’a is usually easy to spot. And the agricultural area and the irrigating channels are in large green areas dotted with villages houses and small roads forming a labyrinth in which it is really easy to get lost.

I found it very useful to print the maps in the nominating papers to find my way to the aflaj (even if the map of Falaj Al-Khatmeen is wrong, and the nominated area do not match the underlying map).

Falaj Daris (Nizwa) is easy to find. It is is clearly signposted a few kilometers north of Nizwa town. (It is not signposted if you drive in the opposite direction). There is a park next to the shari’a, popular with local resident for afetrnoon walk. This aflaj is one of the largest and oldest in Oman. It might look a bit disappointing and I would recommand to visit the two next aflaj.

Falaj Al-Khatmeen (Birkat al-Mouz) lies in a the very nice looking village of Birkat-al-Mouz, some 20 km east of Niza. I stayed at the Golden Tulip Nizwa Hotel (a good choice) which is closer from Birkat than from Nizwa. The shari’a is very easy to spot as it runs under the town’s fort. Dowstream, it passes a mosque (and a place for ablution), and then splits into three equal irrigating channels. From there, you can follow any stream into the agricultural area of the village, with palm trees and mus houses all around. On top of the hills, many watch tower can been seen ; they were used to protect the aflaj. On a small hill above the village is the ruins of the old Birkat-al-Mouz, a very atmospheric abandonned village.

Falaj Al-Malki (in Izki) lies 10 km east of Birkat al-Mouz. The shari’a run under the main road, but is difficult to spot (even with a map). It is easier to leave the main road and get into any part of the old town and go by chance. The old town is a real labyrinth of small roads bordered by mud walls and houses, date trees and other crop fields, but you are sure to find the multiples branches of the irrigations channels. In the middle of this labyrinth lies the ruins of a very large fort. Be ready to get lost in this village. But it is worth the time lost.

Falaj Al-Muyassar (Rustaq) : I went to Rustaq to see the fort (on the TL), just below the fort lie branches of the irrigation channels, even if it is unclaer

Falaj Al Jeela lies high in the mountains, and cannot be easily reached (it probably needs a guide and a 4x4).

Frederik Dawson

Driving from Muscat, the capital city of Oman, to the city of Nizwa was my first time to see Middle East desert environment, I was shocked to witness how dry of the landscape could be, all red lands and dark mountains looked like they had been burned by fire with no single tree or a sign of life except fast driving cars on the road. The desert environment was far worse than deserts in China or Uzbekistan. Then I started to saw communities in the valley along the dry rivers called “Wadi” at first, I understood that the villages survived by seasonal water from the river, but when I visited these villages, it was falaj system that supplied water to the communities.

During my Oman trip I saw Omani Aflaj in many towns and villages, but for UNESCO listed ones, I only saw Falaj Daris in Nizwa which was the biggest falaj in the country and its water sources were just outside the city center on the way along old Nizwa – Bahla road. However, I could not see falaj sources as they were underground, also aboveground were incredibly dry riverbed and full of rocks and gravels that seem to be impossible to have water tunnels underneath such unfriendly terrain. Falaj first appeared aboveground in the newly created park just outside Nizwa next to the dry river. Its appearance was like a small canal with stone wall that covered with mortar. The canal continued into the residential zone and very green plantations in the city passing mosque and a small fort. Unfortunately that Falaj Daris did not match my expectation despite its size and very sophisticated water channels as I had seen the much simpler and smaller one at Misfat Al Abreen where I could see how community managed the water for households and agriculture as well as the separation zone of male and female areas in washing pool area, so I expected some similarities at Nizwa, but Nizwa’s falaj seem to be mainly for agriculture and that made Falaj Daris to be looked like just a normal irrigation system, nevertheless I really enjoyed the plantations along the falaj with interesting plant like date, banana, alfalfa and grass to protect soil and conserve water against desert heat.

For me Omani Aflaj is another good example of World Heritage Site that its outstanding value cannot be seen easily, as there were no visual differences of falaj and other normal irrigation system in any part of the world, if I never had seen a fascinating German documentary about an Omani village that was facing a drying falaj and had to send people to find new water springs along the ancient underground falaj tunnel and its open access shafts many times, I would probably ranked this World Heritage Site among the lowest. From the documentary I found out that Aflaj was fascinating, and I really admired ancient people who dug a complex of tunnels to link springs into the community. Also, falaj did show me how important of water in the desert environment as a key of urban settlement in Oman especially for the city like Nizwa as well as the human abilities to survive and create perfect environment for living and farming, so Omani Aflaj were truly an interesting World Heritage Site of Oman.

John booth

Of all the aflaj in Oman and the UAE, only one that I saw in 2010 is included in this WHS. That is the falaj al Muyassar that flows through Rustaq, and beneath the fort (on WH tentative list). The portion I have seen flows through a date plantation, then beneath the fort, and in an open channel out into Rustaq village. It then continues in an open channel through the village.

In 2011, while staying in Nizwa I visited several others, at Falaj Daris, at a spot where steps are provided for washing prior to attending mosque. The Falaj Al-Khatmeen was easily located at Birkat Al Mawz in a date plantation adjacent to the fort. Less easy to find was Falaj Al-Malki, located in what is now a new housing estate. It was not in a very clean state either.

Solivagant

Most Omani villages possess a falaj irrigation system which collects and distributes water from source to houses and fields. Their origin dates back centuries and they are a central aspect of Omani agriculture and social organisation. However when I saw that “A Falaj system” was on Oman’s Tentative list I had little hope that a single one chosen from among the c3000 in the country would be one that I had seen in 2005! It then appeared that the T list actually called it “Aflaj systems of Oman” and that “aflaj” is the plural – so it was the entire concept which was being proposed! In the event Oman chose 5 such systems as representative of the country’s entire stock and luckily – yes, we had visited 1 of those chosen – the Falaj Daris at Nizwa (photo)

Nizwa has a population of around 60000 and is a tourist center - this, more than the example itself, may have had something to do with the selection (which also increases to 3 the number of WHS within a short drive of this town!). The system is 8 kms long and, as is the way with aflaj, much of the channel from the source is underground (There are 3 types of Falaj and Nizwa’s is a Daoudi which taps into underground water as opposed to using a spring, river or dam. Where the water appears from the tunnels for distribution is called the shari’a and, in Nizwa, a small park has been created there, which is no doubt a pleasant place to escape the summer heat and enjoy the shade and running water. It is clearly signed on the outskirts of town to the right on the road to Bahla. Our photo is of this spot and also shows the cement mortar used in restoration to cap the channels. This caused ICOMOS much consternation (they wanted traditional mortar to be used) and was one of the factors which led them to recommend deferral rather than inscription in 2006 (Quite what caused WHC to ignore this advice in a year when they threw out so many other nominations is not yet clear!). They also disliked the lack of historical documentation of age and the lack of management plans etc. In the background it also seemed that they were concerned as to whether the irrigation systems were, per se, special enough worldwide either in terms of technology or history to justify inscription and very much wanted the whole “Cultural Landscape” aspect to be covered.

Certainly we have seen similar underground water movement technology used in China (There is a good site at Turpan) and in Iran/Turkmenistan (where they are called Qanats) so ICOMOS were right to be concerned about the “Universal Value” of aflaj. As for the 5 sites inscribed, well I can’t comment on the other 4 (Of these the Khatmee is also near Nizwa and the Al Malki is on the main road from Muscat to Nizwa near Izki), but we saw far nicer ones than the Daris at Nizwa. These tended to be in villages – we particularly remember Al Hamra, Tanuf and Misfah near to Nizwa and the A’samdi Falaj near Sumail. Omanis are friendly and courteous - express an interest in the village Falaj and you may be invited in for Coffee and dates (we were!). In the villages you will be more able to see and understand the overall layout and the gradual change in use of the water as it flows – from collection for drinking through male/female ablution areas, clothes washing and finally into the date fields. You will also see the Sun dials used traditionally to time the distribution of water.

To visit Oman and not try to see and explore the Aflaj system would be to miss an important aspect of Omani culture – for that reason this inscription is to be welcomed whatever the merits or otherwise of the sites chosen.

Community Rating

- : Christoph Rahelka Laurine

- : Szucs Tamas Thomas van der Walt Dutchnick Fmaiolo@yahoo.com

- : Vincent Cheung Tarquinio_Superbo Jean Lecaillon

- : Clyde Walter Randi Thomsen Jeanne OGrady Stanislaw Warwas Riomussafer Bin Alexander Barabanov 2Flow2 Els Slots

- : Harry Mitsidis Alexander Lehmann Csaba Nováczky Svein Elias Frederik Dawson Zizmondka Jon Eshuijs

- : Wojciech Fedoruk Philipp Leu Solivagant Hanming Christravelblog Zach Roman Raab Martina Rúčková

- : Philipp Peterer Adrian Turtschi George Gdanski Mihai Dascalu João Aender Luke LOU Ivan Rucek

- : Zoë Sheng Mikko

Site Info

Site History

2006 Advisory Body overruled

ICOMOS advised Referral, for better protection and management plan

2006 Inscribed

Site Links

Unesco Website

Official Website

Related

In the News

Connections

The site has 10 connections

Constructions

Human Activity

Timeline

Visiting conditions

WHS Hotspots

World Heritage Process

Visitors

146 Community Members have visited.

The Plaque

(photo by Clyde)

(photo by Clyde) (photo by Clyde)

(photo by Clyde) (photo by Clyde)

(photo by Clyde) (photo by Clyde)

(photo by Clyde)